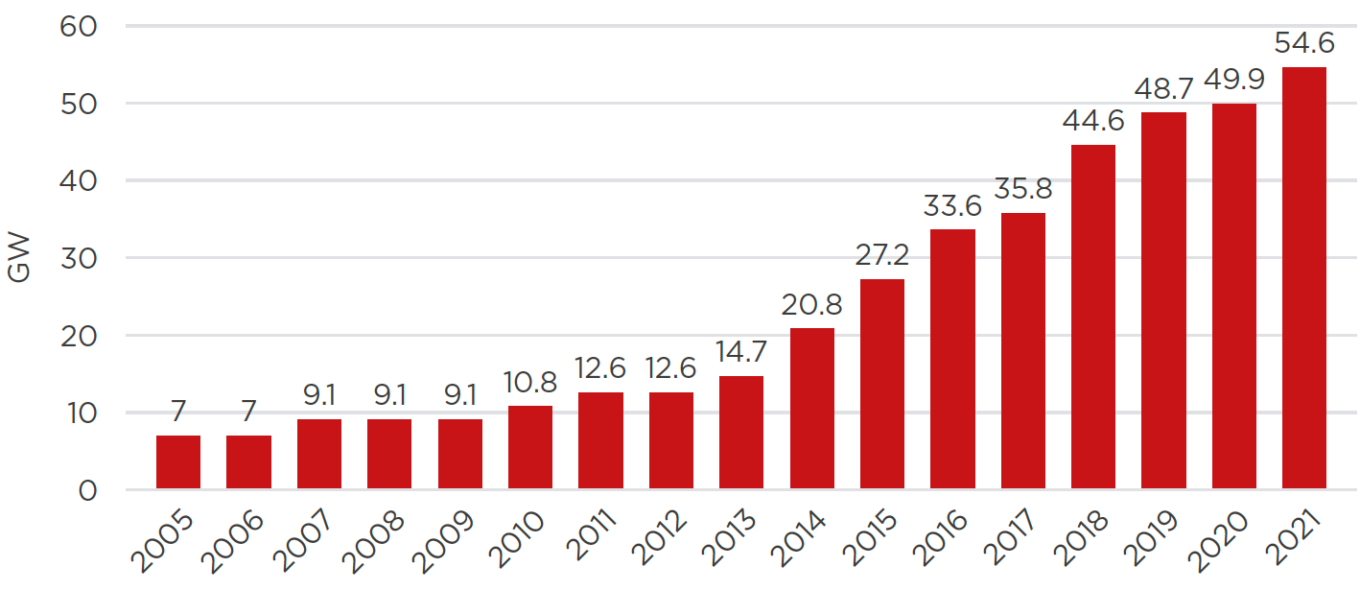

China has the third largest nuclear power fleet in the world, behind only the United States and France. As of September 2022, China’s 54 operating nuclear power units had roughly 52 GW of capacity. 1

Much of the growth of the global nuclear power industry is in China.

- During 2021 and the first 9 months of 2022, 10 nuclear power plants were connected to the grid globally. Five of these were in China.

- During the first nine months of 2022, construction began on 7 nuclear power plants globally. Five of these were in China.

- As of September 2022, about one-third of the nuclear power capacity under construction globally was in China. 2

In 2021, nuclear power provided roughly 4.8% of China’s electricity. Two commercial reactors and one demonstration reactor were connected to the grid. In October 2021, the State Council reiterated that nuclear power will play an important role in peaking carbon emissions before 2030. 3

Background

Construction on the first civilian nuclear reactor in China began in 1985. The program grew slowly with three reactors in operation by 1994. During the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005), the Chinese government launched an ambitious expansion of its nuclear power program, calling for the construction of eight more nuclear plants. That trend continued in the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010), which called for further expansion of the nuclear power program and a focus on Generation III technologies. 4

The Fukushima accident on March 11, 2011, brought the rapid expansion of China’s nuclear program to a halt. China’s State Council ordered an immediate safety review at plants under construction and suspended approvals for new plants, pending a major safety review. In October 2012, a new safety plan was approved and approvals resumed. 5

Between 2011 and 2020, China connected 37 nuclear reactors to the grid. These reactors had approximately 36 GW of capacity, which was roughly 60% of the nuclear power capacity added globally during this period. 6 The growth of China’s nuclear power industry between 2011 and 2020 is one of the fastest additions of nuclear power capacity in history, behind only the US and France between 1979 and 1989 (US: 50 GW, France: 45 GW). 7

In the past decade, at least two nuclear projects in China have been canceled due to strong public opposition. These include a proposed uranium processing plant in Guangdong (canceled in 2013) and proposed nuclear fuel reprocessing facility in Jiangsu (canceled in 2016). 8

All of China’s operating nuclear power plants are in coastal provinces. All nuclear power plants under construction in China are in coastal provinces as well. However three planned nuclear reactors and many proposed nuclear reactors are inland. 9

Figure 7-1: Nuclear Power Capacity in China (2005-2021)

Source: World Nuclear Association (September 2022) 10

Policies

The Chinese government has regularly set ambitious goals for expanding nuclear power. The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) called for 58 GW of installed nuclear power capacity and an additional 30 GW under construction by 2020. 1 Although this goal for installed capacity was missed, the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) set a goal of 70 GW of installed capacity by 2025. 12

The Chinese government supports the development of nuclear power with a number of policy tools:

- First, nuclear power plants often receive favorable prices and allocations of operating hours for electricity sales. While power market reforms have the potential to undermine this favorable treatment, the recent focus of energy security has led to its continuation. 13

- Second, through policy banks such as China Development Bank, the government provides cheap debt capital to the large state-owned enterprises that dominate China’s nuclear power sector (including China National Nuclear Corporation, China General Nuclear Power Group and State Power Investment Corporation).

- Finally, central and provincial authorities help assemble land and arrange for transmission connections at new nuclear power plant sites. 14

In building its nuclear power fleet, China has imported technology from the United States (AP1000), Canada (CANDU), Russia (VVER) and France (M310 and EPR). The Chinese government aims to localize these technologies and become self-sufficient in reactor design and construction.

Chinese policy now mandates using Generation III or more advanced technologies. The 14th Five-Year Plan explicitly identified the new China nuclear technologies to be deployed:

- Hualong One – indigenous design, one in operation, six under construction in China. Two overseas Hualong One reactors are operational in Pakistan.

- Guohe One (CAP 1400) – based on Westinghouse AP1000, one reactor under construction.

- High-temperature gas-cooled reactors – one demonstration plant with two reactors in operation in Shandong Province. These are China’s first Generation IV reactors.

The 14th Five-Year Plan also encourages the development of small modular reactors and floating offshore nuclear power plants. 15

In April 2022, Westinghouse Electric Company announced that China’s State Council had approved construction of four new AP1000 reactors (two in Sanmen, Zhejiang Province and two in Haiyang, Shandong Province). 16

Nuclear waste in China is stored on-site at nuclear power plants and in temporary storage facilities. In part due to the country’s dependence on imported uranium, the government is planning a closed fuel cycle. Testing started at a pilot reprocessing plant in Gansu Province in 2010. A larger demonstration project is under construction at the same site and projected to begin operating by 2025. The possibility of developing a coastal site is also being assessed. 17

Central players in the development of China’s nuclear policies include the State Council, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), National Energy Administration (NEA), National Nuclear Safety Administration (NNSA), Chinese Atomic Energy Authority (CAEA), 18 Bureau of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, and all the major nuclear power companies.

The key laws governing nuclear power include:

- the 2015 National Security Law which mentions the protection of nuclear materials and the need for capacity to respond to nuclear threats and attacks; 19 and

- the Nuclear Safety Law, effective from January 1, 2018. 20

China has no law on nuclear liability. Two “Replies” from the State Council, in 1986 and 2007, provide guidance on this topic. 21 A draft Atomic Energy Law was first proposed in 1984 but never enacted. It was circulated for consultation in 2018 and is tentatively scheduled for deliberation by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in 2022. 22

Regulations directed explicitly at the nuclear industry include:

- 1987 Regulation on the Management of Nuclear Material;

- 1990 Regulation on the Control of Nuclear Material;

- 1993 Regulation on Emergency Measures for Nuclear Accidents at Nuclear Power Plants;

- 2005 Regulation on the Safety Supervision and Administration of Civil Nuclear Facilities.

One key question with respect to the future of nuclear power in China is the siting of nuclear power plants in inland provinces. Safety concerns and public opposition have stalled approvals at inland reactor sites ever since the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011. Due to land constraints in coastal regions, expansion into inland provinces will be needed for significant growth in the Chinese nuclear power sector.

Impact on CO2 Emissions

The Chinese government identifies its nuclear power policies as part of its strategy to fight climate change. 23

China’s nuclear power fleet helps reduce emissions of heat-trapping gases.

- Coal plants and nuclear power plants play similar roles on electric grids, as baseload power. 24

- A nuclear plant emits 95–97% less CO2 per MWh on a lifecycle basis than a coal-fired power plant, 25 which means that a 1 GW nuclear power plant replacing coal-fired power avoids roughly 7 million tonnes of CO2 per year. 26

- If each nuclear plant in China displaces a coal-fired power plant that might have been built in its place, then avoided emissions from China’s nuclear fleet in 2022 (based on roughly 55.8 GW of capacity) would be roughly 390 million tonnes of CO2 per year—approximately 3.5% of China’s CO2 emissions and almost 1% of global CO2

- The NDRC’s Energy Research Institute estimates that China’s nuclear power fleet contributed a reduction of 274 million tonnes of CO2 in 2020. 27 The difference between this estimate and the one above will reflect the lower installed capacity in 2020 as well as possible assumptions concerning coal power plant emissions, nuclear plant operating hours or other factors.

- The China Nuclear Energy Association estimated that the supply of nuclear power during the period January to March 2022 prevented 70.9 million tonnes of CO2 emissions compared to the equivalent amount of coal-fired power. 28

References