In 2021, China was the world’s third largest consumer of natural gas, behind the United States and Russia. Natural gas accounted for 8.6% of China’s primary energy use—a much smaller share than the global average of almost 25%. Approximately 6.5% of China’s energy-related CO2 emissions came from natural gas. 1

China’s central government and its state-owned oil and gas companies support the development of China’s domestic natural gas resources. 2 The conversion of coal heating to natural gas is an important part of the government’s strategy for reducing local air pollution in northern China. Natural gas has potential climate benefits if it substitutes for coal and methane emissions are controlled.

Background

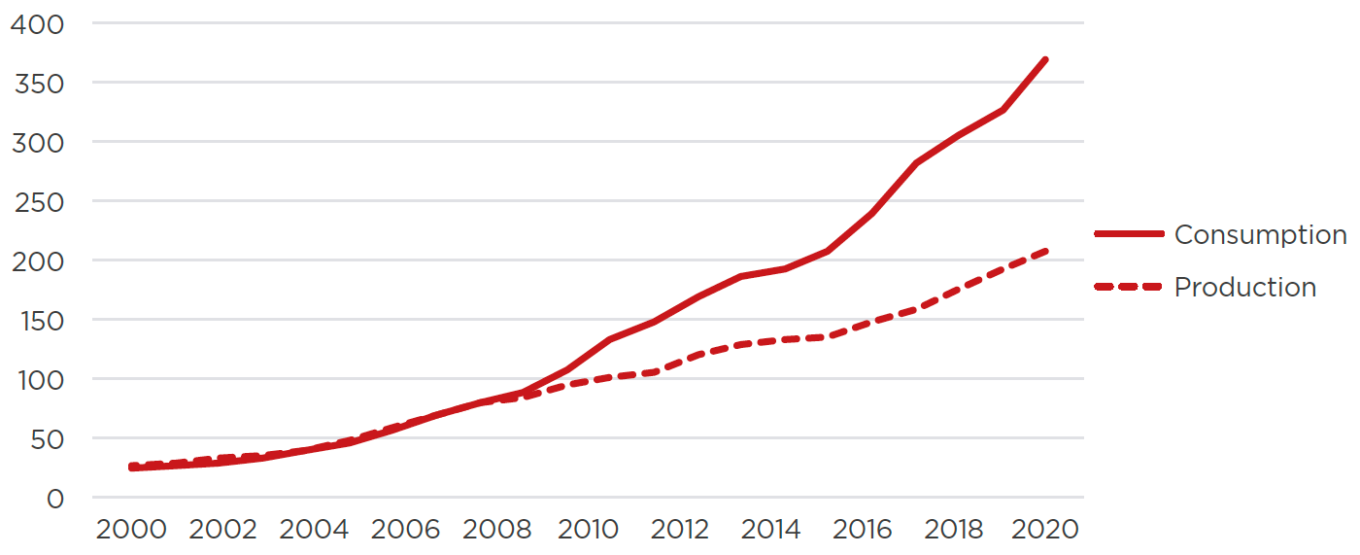

Natural gas use in China has grown significantly in recent years. During the 13th Five-Year Plan (FYP) (2015–2020), China’s natural gas use grew by 70%. In 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, natural gas consumption in China grew by 6.9% (three times GDP growth) to reach 328 bcm. 3 In 2021, gas use grew by 12.6% (almost double GDP growth) to reach 372.6 bcm. 4

Figure 12-1: China’s Gas Consumption and Production (2000-2020)

Source: National Bureau of Statistics 5

Natural gas is used for many purposes in China. In 2020, the principal uses were for industry (46-47% of total consumption), city gas including residential and transport use (37–38%) and power generation (16%). 6

The Chinese government promotes natural gas consumption as a means of displacing dispersed coal in industrial, commercial and residential use. 7 But the availability and cost of gas have been limiting factors. In 2017–2018, when the government-mandated coal-to-gas switch in northern China led to price spikes and supply shortfalls, 8 the government amended the policy guidance to allow switching from dispersed coal to coal-powered electric stoves. Coal-to-electricity was also permitted, provided that this eliminated small industrial coal-fired steam boilers. The main policy priority was to reduce pollution from fine particulate matter (PM2.5), not carbon emissions. 9

Gas plays a small role in China’s power sector, accounting for roughly 6% of installed capacity. 10 This is a much smaller share than in the EU or the US, where gas represents over a third of gas in power, but a 72% increase since 2015. 11 While expensive imported gas, costly turbine technology and the lack of fully competitive electricity and carbon markets in China have limited the role of gas in China’s power sector, its use is set to increase in the coming years due to the growing need for power system flexibility and government’s aim to limit the use of coal in the power sector.

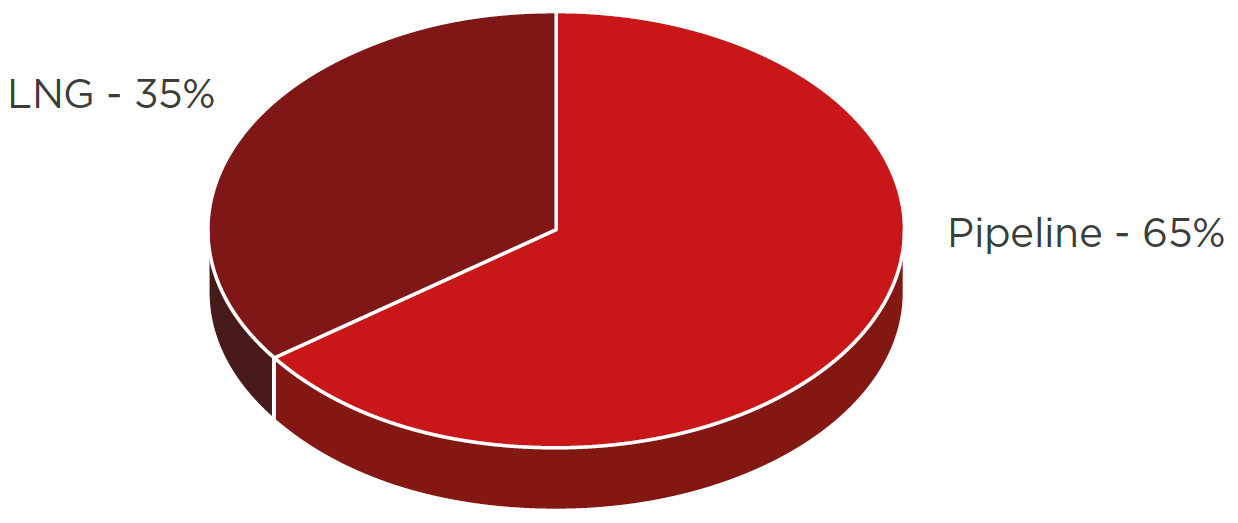

China’s natural gas comes from three sources: domestic production, pipeline imports and imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Historically, most of China’s natural gas has come from domestic production, mainly from conventional wells. In 2020, domestic production reached 192.5 bcm, just shy of the 13th Five-Year Plan target of 207 bcm. 13 At the end of 2021, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, domestic output grew further to reach 205 bcm, rising year over year by 8.2%. 14 In the 13th FYP, domestic output rose by close to 60 bcm, from 135 bcm. In the 14th FYP, China is aiming for a more modest increase in domestic production, reaching 230 bcm by 2025.

China has substantial proven reserves of shale gas but much of it is very deep, in mountainous areas and challenging to produce. Shale gas production in 2020 reached 20 bcm, a large 32% year-over-year increase, and a sharp rise from the 4.5 bcm produced in 2015, 15 although this was still short of the government’s targeted 30 bcm by 2020. 16

At the same time, China produced 6.7 bcm of coal-bed methane 17 in 2020, falling short of the 13th FYP target of 10 bcm, and 4.7 bcm of synthetic gas (syngas). While the production of gas from coal seams helps China in its quest to produce more gas domestically and mitigate its reliance on imported sources, coal-bed methane and syngas create environmental challenges, with syngas in particular increasing CO2 18

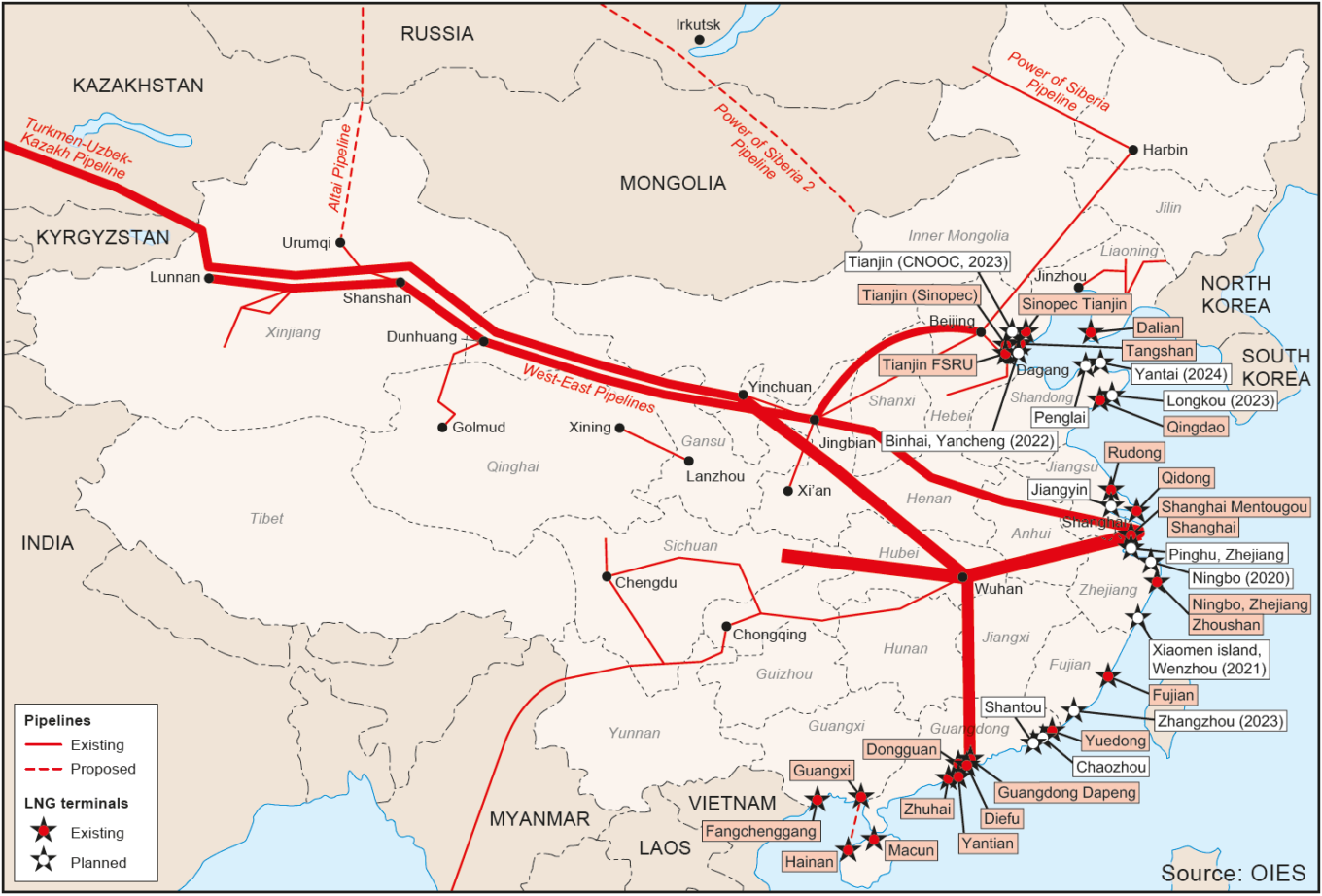

China currently imports natural gas through three pipeline systems: the Central Asia gas pipeline system (from Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), with a capacity of 55 bcm and the China-Myanmar pipeline, which has 12 bcm capacity. In December 2019, the Power of Siberia pipeline from Russia began operating. The pipeline is designed to deliver 38 bcm to China and is expected to reach full capacity in 2024–2025 as the infrastructure to expand deliveries within China is being added and Russia increases production at the fields supplying the pipeline. Total pipeline imports in 2020 reached 47.7 bcm, 19 representing a 15.7 bcm increase over the course of the 13th FYP, from 32 bcm in 2015. In 2021, however, pipeline imports reached 59 bcm and with higher volumes expected through the Power of Siberia, they may temper the growth in LNG imports.

In 2020, Chinese LNG imports reached 89 bcm, surging from 25 bcm in 2015. Much of the demand increase was is due to coal-to-gas switching. The strong growth in demand, combined with efforts to liberalize the market and allow more non-state players to import gas, led to a large increase in LNG import terminals. In 2021, China had an estimated 90 Mtpa of LNG import terminal capacity. The country more than doubled its LNG terminal capacity over the course of the 13th FYP 20 and is set to add as much as 100 Mtpa by 2025. 21 China also continues to add domestic pipeline capacity.

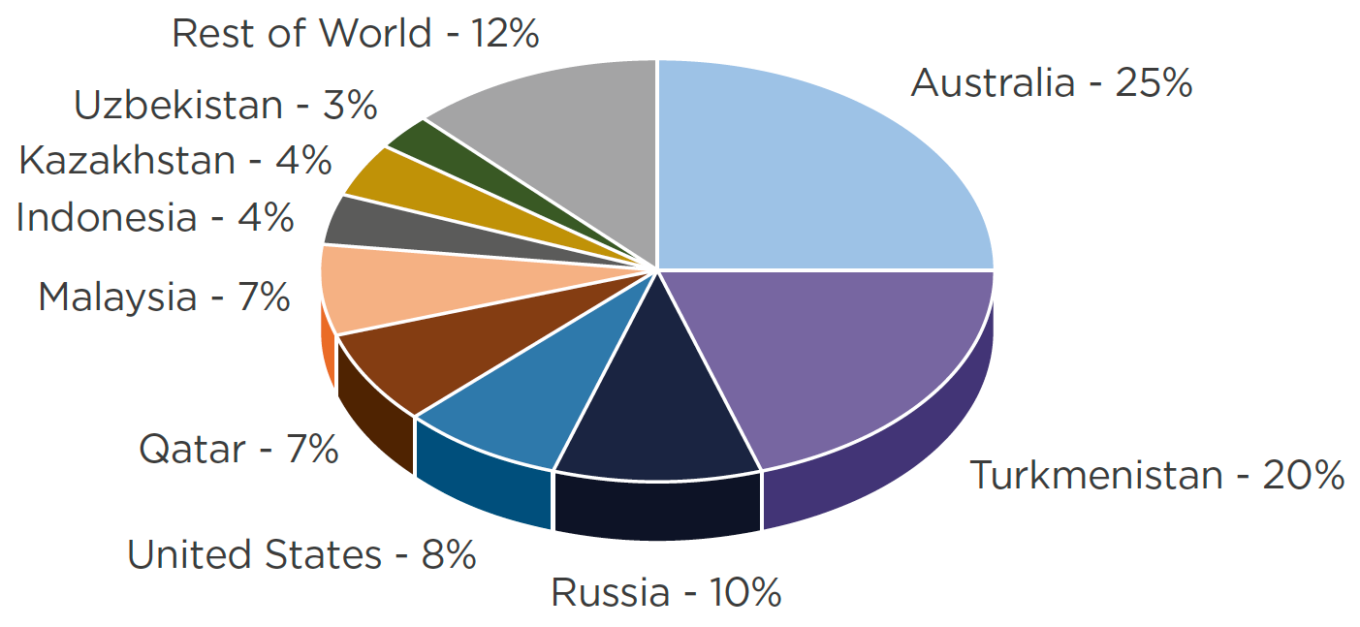

Figure 12-3: China’s 2021 Natural Gas Imports by Country

Source: General Administration of Customs accessed via Argus

Production and Consumption Goals

Government policy documents focus on ensuring supply security and operational flexibility in the domestic gas markets.

The 14th FYP includes a target for domestic production to reach 230 bcm and, more broadly, highlights efforts to increase domestic reserves and output of both conventional and unconventional gas sources.

The 14th FYP also aims for gas storage to reach 55–60 bcm, or 13% of total consumption (suggesting an implicit demand guidance of 430–460 bcm in 2025). The storage additions are ambitious given that in 2020 China held 14 bcm of underground storage capacity.

The 14th FYP discusses the need to develop the pipeline infrastructure as well as the digitization and technological upgrade of the energy sector, including the oil and gas sector.

These operational improvements are also aimed at encouraging third-party access to the gas both upstream and downstream as the government continues to pursue market reforms.

The 14th FYP does not, however, specifically address the role of natural gas in the energy mix or in the dual carbon targets. It does not include an explicit goal for the share of gas in the energy mix, nor does it include a target for the share of gas in installed power capacity. It does, however, clearly envisage a role for gas in the power sector to help manage intermittency. 22

China’s National Energy Administration’s (NEA) Natural Gas Development Report in 2021 estimates that gas consumption will reach 550–600 bcm in 2030 23, in line with Tsinghua’s University’s estimates of demand reaching 580 bcm that year, or 13% of the energy mix. By 2040, however, views diverge with Tsinghua’s forecast of demand falling to 340 bcm, while the State Grid’s energy research unit expects 600 bcm of demand. Meanwhile, China’s largest natural gas producers, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and Sinopec, forecast that gas demand will peak in 2040 at 650 bcm and 620 bcm respectively. 24

Market Reforms

Historically, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) set natural gas prices by adding production costs, transmission costs and fixed margins. Gas prices have been kept high for industrial users to help cover the costs of subsidizing residential gas use. In recent years, a growing percentage of Chinese nonresidential natural gas sales have been priced based on market value. Citygate tariffs for residential users are being deregulated as well. These price reforms are intended in part to bring down the cost of natural gas for industrial users, encouraging the switch from coal to natural gas. 25 Given the price volatility in global markets in late 2021 and early 2022, further liberalization of prices may be stalled.

Structural changes are also underway in China’s natural gas pipeline network. Historically, CNPC and Sinopec controlled most of China’s long-distance natural gas pipeline network. But the creation of the China Oil & Gas Piping Network Corporation (PipeChina) in December 2019, stripped the state-owned majors of their interprovincial pipelines as well as some of their LNG receiving terminals. The creation of PipeChina, a state-owned company, was intended to provide fair and open access to pipelines, LNG import terminals and storage facilities, given the state-owned majors’ reluctance to grant third-party access to the infrastructure. Ultimately, Beijing hopes that the new midstream company will further support the liberalization of both the upstream and midstream. 26

Investors in the upstream had struggled to market their production in the large consumer areas given the transport constraints, while private LNG suppliers could not use the country’s LNG terminals. If PipeChina manages to increase transparency and optimize gas supplies in China, it could spur demand. But from a climate change perspective, as discussed above, a higher share of gas in the energy mix is conducive to China’s carbon footprint only if it displaces coal and/or if the carbon is sequestered.

Environmental Standards

China does not have regulations addressing methane leaks from natural gas production, transport or use. China is a Partner Country in the Global Methane Initiative, “an international public-private partnership focused on reducing barriers to the recovery and use of methane as a clean energy source.” CNPC is a member of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, a voluntary industry initiative working to reduce methane emissions. 27

In May 2021, China’s Oil and Gas Methane Alliance was inaugurated. The Alliance includes seven members: the three large state-owned oil and gas companies (CNPC, Sinopec and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC)), as well as PipeChina, Beijing Gas, CR Gas and ENN Energy. The founding members pledged to control methane emissions across the entire industry chain. Member companies have further pledged to “strive to reduce the average methane intensity in natural gas production to below 0.25% by 2025 […] and work to reach world-class level by 2035”. 28

China did not sign the Global Methane Pledge, which was released in connection with COP26 in November 2021 and has now been signed by more than 100 countries. At COP26, the Chinese government announced it would produce a national action plan to control methane emissions prior to COP27 in November 2022. The 14th FYP also seeks to “strengthen the recovery and utilization of methane in oil and gas fields”. In the US-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s, published in November 2021, the US and China committed to work together to bolster monitoring, management and research of methane emissions over the next ten years.

Climate Change Impacts

The climate change impacts of natural gas use are complicated and controversial.

On the one hand, burning methane (the principal component of natural gas) produces roughly half the CO2 emissions per unit of energy as burning coal. Conversion of China’s vast coal-based heating and power infrastructure to natural gas could significantly reduce Chinese CO2 29

On the other hand, each molecule of methane has roughly 84 times the warming impact of a molecule of CO2 over a 20-year period and roughly 28 times the warming impact of a molecule of CO2 over a 100-year period. As a rough rule of thumb, if more than 3%–8% of natural gas leaks during production, transport or consumption that would cancel the climate change benefits of switching from coal to natural gas. There are very little data on the extent of methane leakage in China. 30

In addition, new natural gas infrastructure such as pipelines and receiving terminals will likely last for decades, creating carbon lock-in and potentially slowing a move away from natural gas and toward renewables or other solutions in hard-to-abate sectors. 31

The climate change impacts of natural gas use in China are uncertain. Natural gas in China often displaces coal, reducing CO2 emissions as a result. (The 13th Five-Year Plan for Gas Development stated than when natural gas use in China reached 360 bcm—a level attained in 2021—CO2 emissions from that natural gas would be 710 million tonnes fewer than CO2 emissions from coal of the same calorific value). 32 However there is little data with respect to methane leakage in China. Such leakage could partially or completely offset any climate change benefits from lower CO2 emissions.

References