China’s largest debt financing channels for outbound investment projects are government-owned.64 These include two policy banks––China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim)––as well as other state-owned financial institutions. Many of these institutions have also been important participants in the growth of green finance in China. (See Chapter 20.) China also plays a leading role in multilateral financial institutions including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank.

All of China’s largest state-owned financial institutions are among the original 27 signatories of the Green Investment Principles (GIP), announced in 2019 as a set of principles for “greening investment in the Belt and Road.”65 The seven principles are high-level commitments around corporate governance, risk assessment, environmental disclosure, green finance, green supply chain management and collective advocacy. There are forty-one signatories today, including major international financial institutions such as BNP Paribas, Swiss RE and Mizuho Bank.66

The following section profiles the policy banks and multilateral development banks in more detail.

(i) Policy Banks

Within the key sectors for the low-carbon transition, the most important debt financiers of Chinese outbound investment have been two “policy banks”: China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim).67

(a) Background

China Development Bank (CDB) is one of the world’s largest financial institutions. At the end of 2021, its assets were RMB 17.17 trillion ($2.70 trillion)68 and loan balance was RMB 12.79 trillion ($2.01 trillion).69 Were it a commercial bank, it would be the 10th-largest in the world.70 Its assets are around four times that of the whole World Bank Group.71 CDB’s annual report lists as the sixth of its “eight key areas … the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)”: “international cooperation in industrial capacity, equipment manufacturing, infrastructure connectivity, energy and resources, and Chinese enterprises ‘going global.’”72 (Other areas are domestic-focused, covering spheres such as infrastructure and basic industry, urban-rural integration and “programs essential for national competitiveness” such as industrial upgrading and energy efficiency.)

China Exim is an export credit agency focusing specifically on supporting Chinese trade and outbound investment. Its annual report states its areas of activity as “foreign trade, cross-border investment, the Belt and Road Initiative, international industrial capacity and equipment manufacturing cooperation, the ‘going global’ endeavors of science and technology, cultural industries as well as SMEs, and the building of an open economy.” It had RMB 5.45 trillion ($0.86 trillion) in total assets and RMB 4.33 trillion ($0.68 trillion) in loans and advances at the end of 2021.

Both China Development Bank and China Exim were established in 1994.73 They operate under the direct leadership of the State Council, China’s chief administrative authority. They are owned solely by the Chinese government and are funded by bond issuances backed by Chinese sovereign credit.74 Both institutions have a variety of financial offerings, from loans and loan guarantees to equity investments, but their portfolios differ; CDB’s credit portfolio consists mostly of loans, whereas China Exim’s is split more evenly between loans and loan guarantees.75 China Exim is also allowed to issue loans at concessional (preferential) rates, which CDB cannot do.76 For both banks, domestic clean energy lending far exceeds outbound clean energy lending.

CDB is China’s largest source of green credit today and has an action plan around green finance and carbon emissions that includes portfolio-wide targets. China Exim has not publicized a low-carbon or climate policy plan, though it has had guidelines on environmental and social impact assessments for outbound loans since 2007. As noted above, both CDB and China Exim signed the Green Investment Principles in 2019. That said, as a general matter, their clean energy lending for domestic projects far exceeds such lending for international projects.77

(b) Outbound Footprint

Limited official information is available on CDB and China Exim’s outbound lending portfolio. Media reports on CDB’s website state that the bank had loaned “more than $260 billion to projects linked to the [BRI].”78 Neither bank provides information on the size of its green credit provisions associated with outbound activity, though bond-level reporting offers some information. For instance, around $150 mn from CDB’s 2017 green bond issuance on international debt markets has been allocated to projects in Pakistan.79

Some of the databases noted in Section C collect information on CDB and China Exim outbound lending from public sources. AidData’s records suggest that these banks accounted for 75% ($585 billion) of outbound loan-financed projects and commitments by Chinese government and state-owned institutions between 2000 and 2017.80 The WRI COFI dataset finds that these banks have also dominated Chinese outbound lending for coal-fired generation, with an 87% share between 2000 and 2020.81

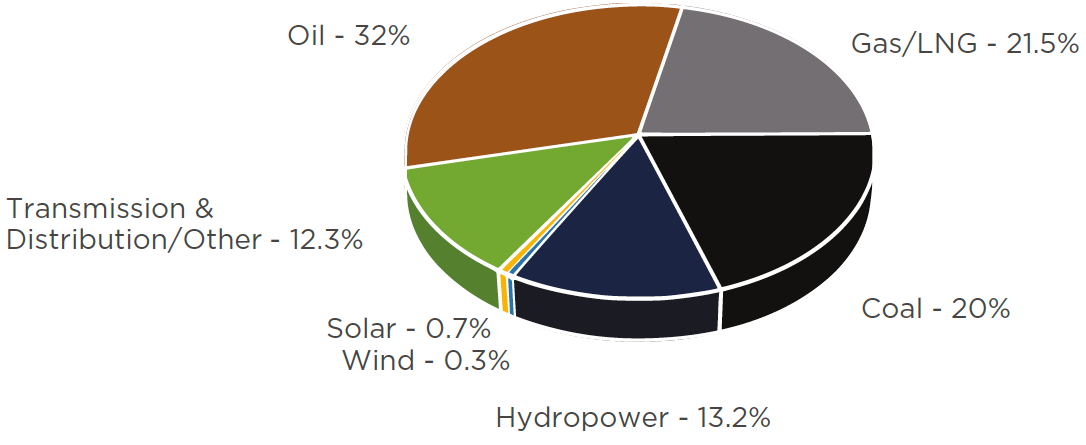

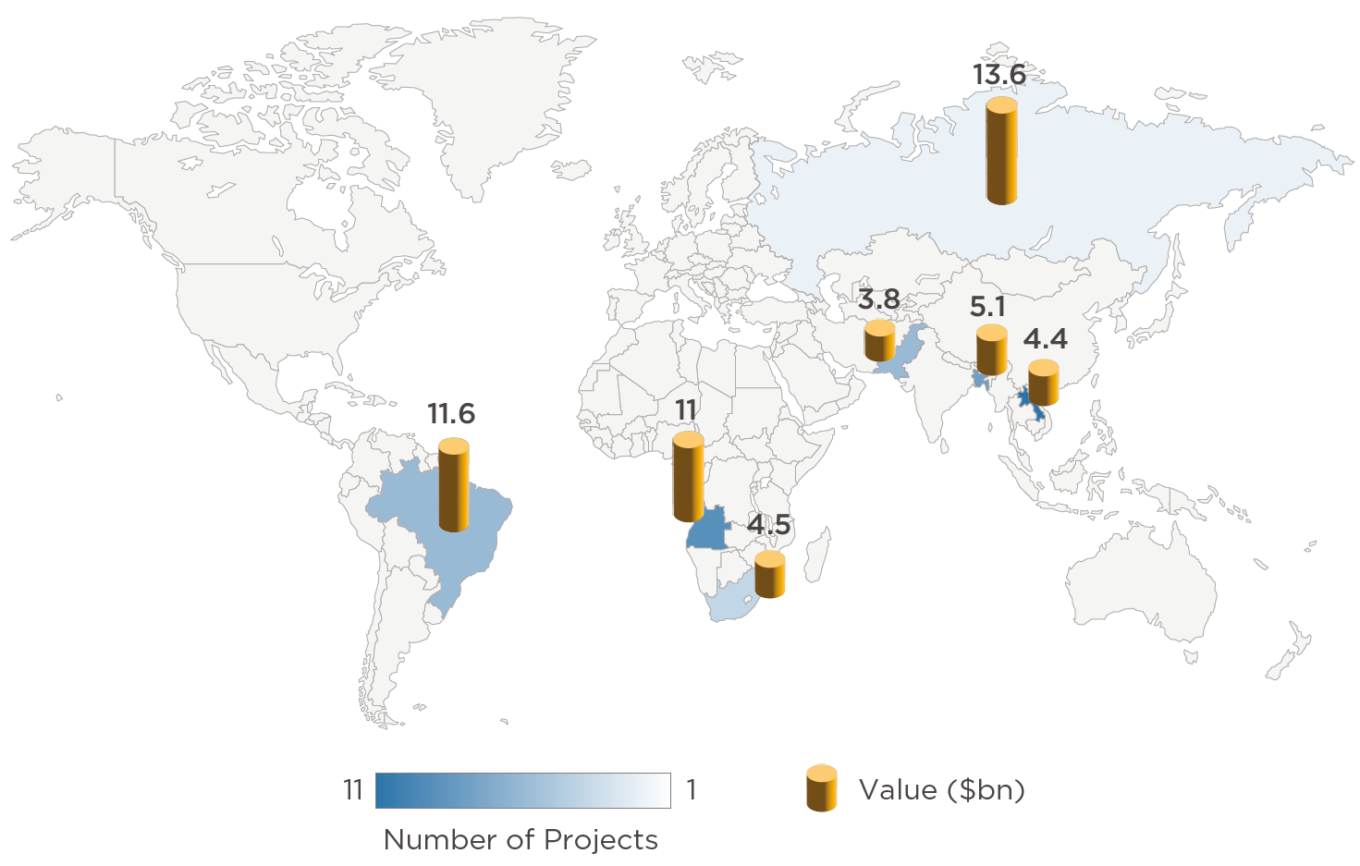

The China’s Global Energy Finance dataset records $136 billion in energy-sector lending by CDB and $83.4 billion by China Exim between 2000 and 2021, in addition to $14.8 billion in co-financing by the two (Figure 26-1).82 Around 70% of recorded CDB loans go to the oil and gas sectors, with Angola and Brazil the leading recipients (Figure 26-2). China Exim’s portfolio accounts for most of China’s lending in hydropower and renewables, though renewables lending has been quite small thus far. Wind and solar make up just 1% of total lending activity in the past five years and four of the five such projects were announced in 2016–17.

Figure 26-2: China Development Bank and China Exim Energy-Sector Lending: Largest Recipients (2016–2021)

Source: Boston University Global Development Policy Center83

Figure 26-3: China Development Bank and China Exim Energy-Sector Lending: Largest Recipients (2016–2021)

Source: Boston University Global Development Policy Center

The CGEF team reports that, since 2016, these two banks’ combined lending of $75.1 billion to “foreign governments and associated entities in the energy sector” is “more energy sector loans provided to public entities than by any other lender in the world.”84 But more than three-quarters of that activity took place in 2016 and 2017, with outbound lending declining steadily from 2018.85 In 2021, the database recorded “no new energy development finance commitments … to foreign governments.”86

(ii) Multilateral Development Banks

China is an important shareholder in a pair of multilateral development banks established in the past decade, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB). These are not instruments of the Chinese state akin to the policy banks and other state-owned institutions. As multilateral banks, their ownership and voting shares are distributed across all member countries. China is the largest shareholder in the AIIB (30%) and an equal shareholder in the NDB with its four other founding countries.87 These banks’ assets are also much smaller than the policy banks discussed above. That said, several features make them worthy of discussion here: China was a leader in their establishment, especially the AIIB, and their sectoral focus overlaps with the BRI’s emphasis on infrastructure and connectivity.

(a) Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) describes its vision as “a prosperous Asia based on sustainable economic development and regional cooperation.”88 China first proposed its establishment in 2013 and waged a successful diplomatic campaign over several years to bring countries on board as members. The bank started operations in 2016 with a Beijing headquarters.

As of December 31, 2021, AIIB had assets of $40.2 billion and $12.3 billion in loan investments across over 100 member countries.89 China is the largest shareholder (30%). It has the biggest voting share (26.6%) in the AIIB’s Board of Governors, its highest decision-making body; the next largest shares are India (7.6%) and Russia (6.0%).90

The AIIB presents its focus as “financing Infrastructure for Tomorrow”: “green infrastructure with sustainability, innovation and connectivity at its core.”91 Its Environment and Social Framework, most recently updated in May 2021, includes requirements around project design and implementation “in accordance with the aims of the Paris Agreement, including the Member’s nationally determined contributions.” 92It also requires ex-ante project heat-trapping gas emissions estimates for projects expected to produce significant emissions.

The AIIB released several new commitments and initiatives around climate issues in 2020–21:

- In 2021, it announced that it would “align its operations with the goals of the Paris Agreement” by July 1, 2023. It also announced a target of a 50% share of financing approvals for “climate finance” by 2025. (Its share in 2020 was 41%.)93

- In 2020, AIIB president Jin Liqun pledged that the bank was “not going to finance any coal-fired power plants” or “finance any projects that are functionally related to coal—for example roads leading to the plant or transmission lines serving coal power.”94

The AIIB launched an update process for its energy sector strategy in December 2021. The draft strategy as of April 2022 incorporates these new commitments and

reflects … the transitioning environment in the energy sector, and pays particular attention to strengthening its guidance on fossil fuels. Recent years have seen elevated climate change commitments and actions from both

governments and the private sector. This necessitates increased action, including new restrictions and conditions on fossil fuel investments.95

As of July 2022, AIIB has provided $5.8 billion in financing across 33 projects in the energy sector since 2016.96 Its biggest energy projects in the past three years have included $500 mn for LNG facility construction in northern China (2019) and several $300–$400 mn projects for power grid strengthening in India and Indonesia (2021). It has also financed investments in hydropower, renewables, waste-to-energy and gas power generation capacity. Outside of energy, major projects linked to the low-carbon transition include $1.3 billion for rapid transit projects in India since 2019.

(b) New Development Bank

The New Development Bank (NDB) was established in 2015 by the five “BRICS” countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.97 Its headquarters are in Shanghai. Each member country pledged a capital subscription of $10 billion, with $2 billion paid in.98 As of December 31, 2021, the NDB reported $24.8 billion in assets and $14.0 billion in loans and advances.99 Its members include the five founding countries, as well as Bangladesh and the United Arab Emirates who joined in fall 2021.100 The five founders control equal voting shares.

The New Development Bank describes its purpose as “financing infrastructure and sustainable development projects in BRICS and other emerging economies and developing countries.”101 Its Environment and Social Framework, last updated in March 2016, directs potential clients to address climate change in their environment and social project assessments as follows:

Assess both the potential impacts of the project on climate change as well as the implications of climate change on the project and develop both mitigation or adaptation measures as appropriate. Identify opportunities for no- or low-carbon use, where applicable, and for reducing emissions from the project.102

As of June 2022, NDB has approved 77 financing projects.103 These included 14 “clean-energy” projects for a total of $4.25 billion, though several are for gas and coal. All but one of these projects, however, was approved in 2019 or earlier. Projects since 2020 include a $500 mn loan to Brazil for mitigation and adaptation projects that can deliver 4 mt in CO2 emissions reductions by 2030, as well as $1.25 billion for rapid transit projects in India and China.

References