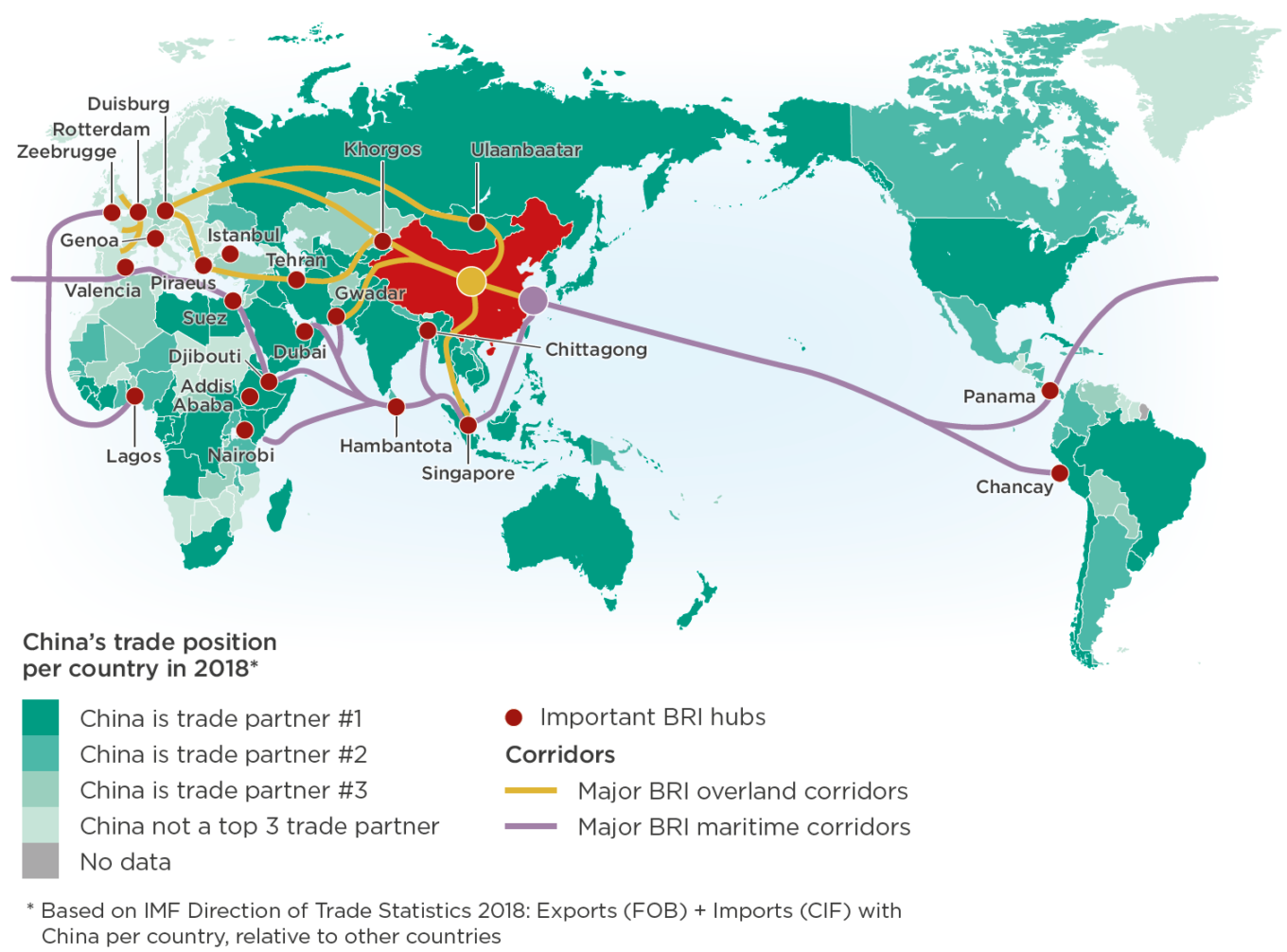

The Belt and Road Initiative emerged from a pair of concepts proposed by Xi Jinping in fall 2013: a “Silk Road Economic Belt” running overland from China via Central Asia to Europe, and a “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” connecting China and Southeast Asia.2 These connectivity visions were subsequently yoked together as a broader initiative, the BRI, and developed into a cross-cutting policy framework for Chinese outbound economic engagement, particularly with the Global South.3 As of late March 2022, the Chinese government reports having signed agreements around BRI cooperation with 149 countries, including 52 from Africa, 38 from Asia, 27 from Europe (mostly in Central and Eastern Europe), 21 from Central and South America and the Caribbean, and 11 from Oceania.4

The notion of connectivity invoked in BRI documents is a broad one. Key white papers from 2015 and 2019 discuss “five connectivities” in measuring the BRI’s impact: policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade facilitation, financial integration and people-to-people ties.6 Infrastructure projects have been a particularly prominent piece of these efforts, as discussed below.

The BRI enjoys a high-profile formal position within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) by way of its incorporation into the Party’s Constitution in 2017, alongside a series of other concepts and initiatives associated with Xi Jinping.7 President Xi provides periodic guidance on the BRI in a variety of venues, such as annual CCP Congresses and the Belt and Road Forums for International Cooperation (held in 2017 and 2019).8 The most senior dedicated body for the BRI is the inter-ministerial Leading Group for Promoting the Belt and Road Initiative, established in 2015.9 Its chair is Vice Premier Han Zheng, who is one of seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the apex decision-making body in the Chinese party-state. The group’s secretariat is housed in the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s most powerful economic policymaking body.10

At the same time, a focus on high-level institutions obscures the bottom-up dynamics that drive financing and project contracting decisions under the BRI umbrella.11 Under the BRI, host countries and the Chinese enterprises and financiers with whom they partner have substantial decision-making authority. Central government agencies, including the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), as well as provincial governments, determine how high-level guidance is translated into concrete policies and projects. In this way, the BRI is not so much a top-down, tightly-managed plan as a vessel for competing interests across firms, ministries, provinces and host countries¬.

References