China is the world’s largest consumer and producer of coal. In 2021, its coal consumption and production accounted for more than half the world’s total. Each year, for the past decade, more than 20% of global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels have come from coal combustion in China. 1

Chinese policy makers have plans to “strictly control” coal use during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025) and start phasing down coal use during the 15th Five-Year Plan period (2026–2030). 2 However, new coal mines and coal-fired power plants continue to be built in China on a significant scale. Concerns about energy security and power sector reliability, as well as promotion criteria for provincial officials, are among the reasons.

This chapter provides background on China’s coal consumption, production and policies.

Background

Coal Consumption

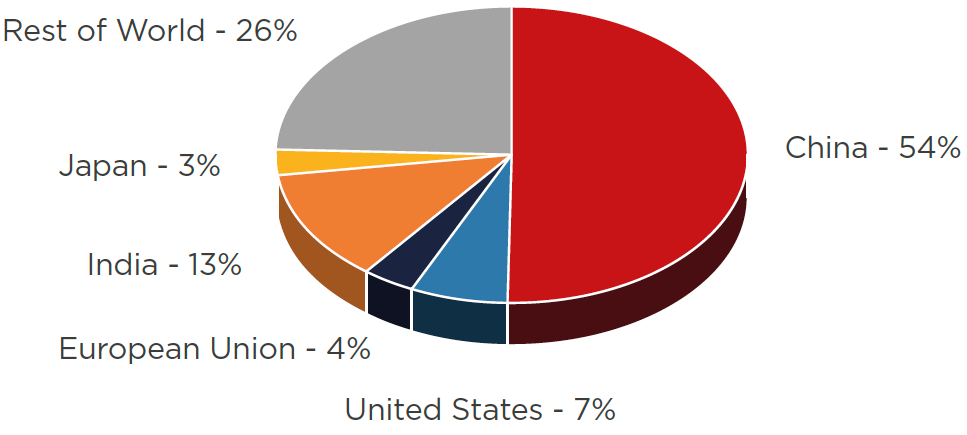

China uses more coal than the rest of the world combined, with roughly 54% of global consumption in 2021. 3

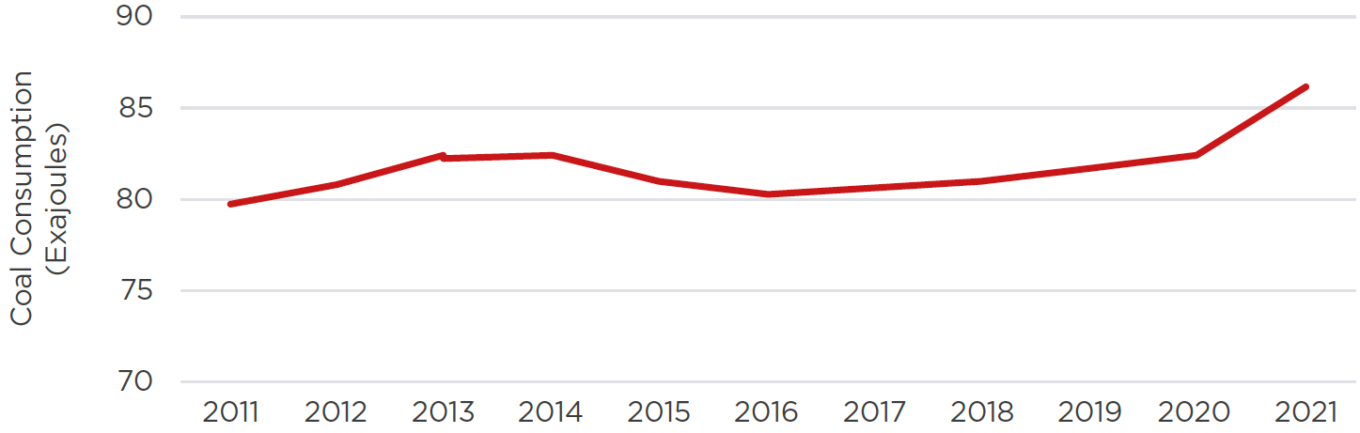

From 2013 to 2020, coal use in China was roughly flat due to slowing economic growth and government policies to limit coal consumption. Since then, coal consumption has increased and then decreased sharply.

- In 2021, coal consumption in China grew by almost 5% as energy-intensive industries led the economic recovery, and some previous policies to limit coal use were relaxed. Chinese coal consumption reached its highest level ever, exceeding the previous peak set in 2013–2014. 5

- In the first half of 2022, coal consumption decreased roughly 2-3% year-over-year according to preliminary estimates. China’s economic growth during this period slowed due to COVID lockdowns and other factors. 6

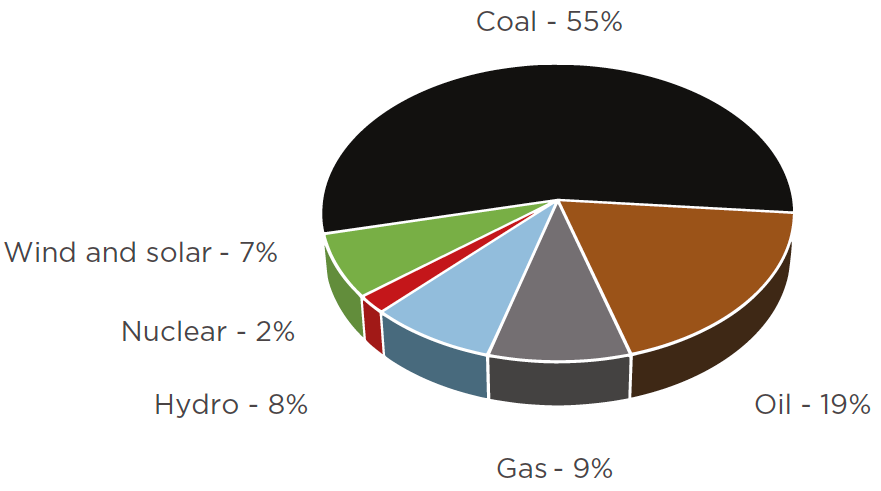

In 2021, 56% of primary energy consumption in China was from coal, according to official statistics. In 2020, coal’s share was 57%; in 2015, it was 64%. Coal’s share of primary energy was more than 70% in the mid-2000s and has fallen steadily since. 8

China’s coal consumption is closely linked to the country’s industrialization. Between 2002 and 2013, coal accounted for 77% of the increase in primary energy demand, driven mainly by coal consumption in the cement, chemical and steel sectors (including both direct coal use and power from coal-fired power plants used in these sectors). 10

Coal is widely used in China for generating electricity, producing heat and as an industrial feedstock. In 2020, 60% of coal was used for electricity and heat generation. Industry accounted for an additional one-third of demand, with buildings, agriculture and non-energy use representing another 7%. 11

Coal-Fired Power Plants

In 2021, 62.6% of China’s power generation came from coal. This was a slight decrease from 2020 when the figure was 63.3%. 12

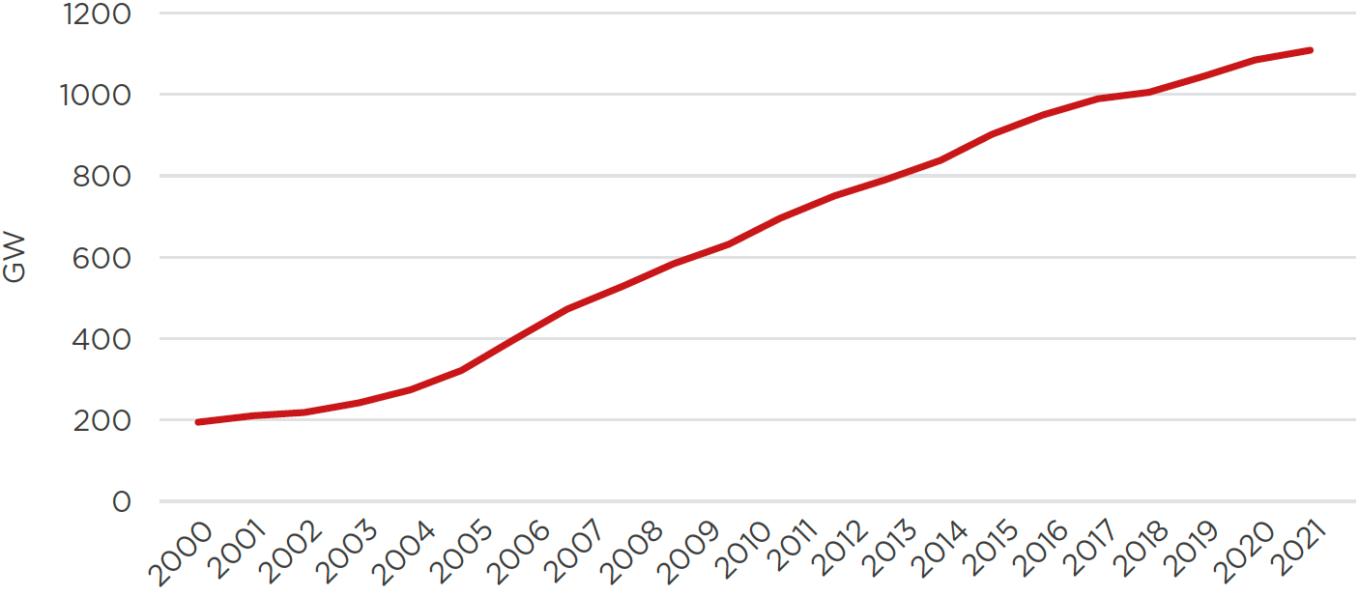

At the end of 2021, China had 1100 GW of installed coal-fired power capacity—more than half the world’s total. 13

Figure 5-4: Chinese Coal Power Plant Capacity (2000-2021)

Source: Carbon Brief; China Energy Portal, Global Energy Monitor 14

More than 25 GW of new coal-fired plant capacity was added in China in 2021—56% of the new capacity worldwide. At the same time, retirements slowed down, dropping to an estimated 2.1 GW—the lowest in more than a decade. 15 Construction also started on 33 GW of new coal-fired plants—the most since 2016.

In the first quarter of 2022, the Chinese government approved the construction of 8.6 GW of coal-fired capacity, according to Greenpeace. 16 Meanwhile, China installed 7.3 MW of coal-fired power plants in the first half of 2022. 17

Construction of coal-fired power plants continues in China for a number of reasons:

- First, electricity demand is projected to rise in the years ahead, propelled by ongoing urbanization, economic growth, the expansion of energy-consuming industries such as data centers, and electrification of vehicles and space heating.

- Second, energy security concerns are prompting the government to prioritize domestic resources, in particular coal. 18

- Third, grid planners need a way to balance variable renewable power. Natural gas serves this function in much of the world, but China’s domestic natural gas supplies are limited and increasing import dependence is not attractive, especially with global gas prices surging in 2021 and 2022.

- Fourth, the coal industry is at the heart of local economic growth and job creation for some provinces. In 2021, the coal sector supported more than 2.7 million jobs in China. 19

- Fifth, promotion criteria for local and provincial officials often emphasize short-term GDP growth, which can be strengthened with construction projects even if the capacity is not needed in the long-term. 20

- Sixth, provincial leaders are often reluctant to share electricity across provincial lines (sometimes called a “Provincial fortresses”), leading to construction in one province even if electricity-generating capacity is available next door. 21

- Seventh, China’s steel, cement and chemicals industries rely on coal as a feedstock as well as on cheap coal-fired electricity and therefore have an interest in maintaining coal production in China.

- Finally, some policymakers are concerned that the switch from coal to other fuels could raise energy costs, thereby exacerbating inflationary pressures and leading to unemployment. 22

While China continues to add capacity, coal-fired power plants operated an average of 4448 hours in 2021 and 4216 hours in 2020, or roughly half the 8760-hour theoretical maximum. 23 (Overcapacity is widespread throughout Chinese industry, not just in the power sector.) In provinces where hydropower dominates, such as Sichuan, Yunnan and Guangxi, coal is often used for power generation only during the dry season or in response to peak load. Annual utilization for coal plants in these provinces has been around 2000 hours for a long time. Nevertheless, local authorities keep the plants online in order to maintain system reliability. 24

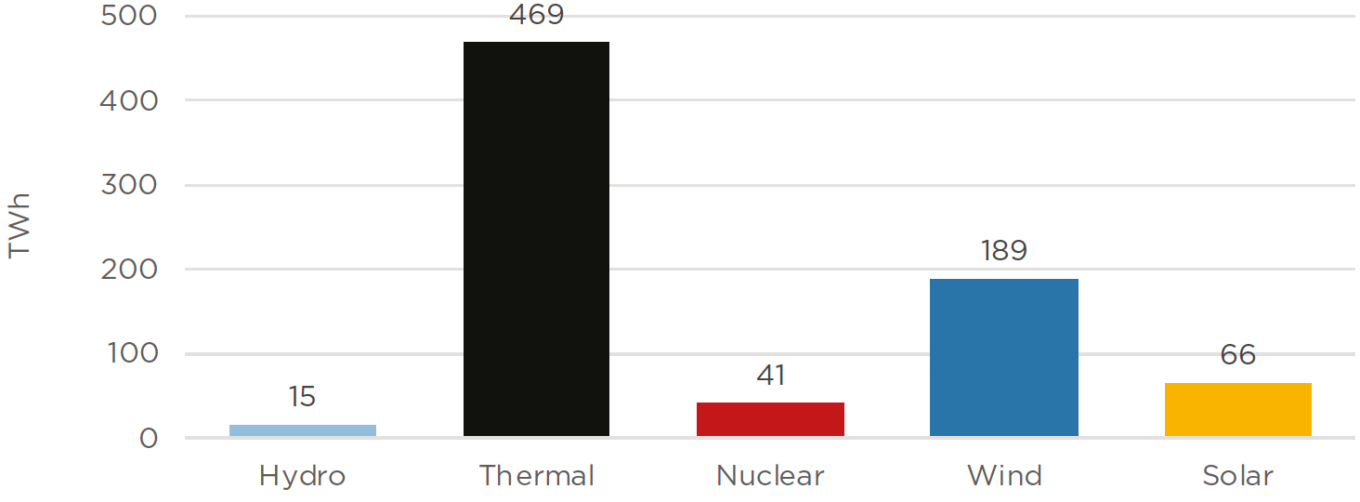

Figure 5-5: Annual Increase in Electricity Production in China (TWh) (2021)

Source: China Electricity Council 25

The extent of overcapacity in China’s coal-fired power plants stems in part from a 2014 central government decision to transfer approval authority for plants to the provincial level. Many provincial governments propped up demand for local coal, in order to make regional employment and production targets. Local governments collectively approved 169 GW in less than a year as they sought to prop up demand for local coal to reach these targets. 26

This surge of new projects came as demand for coal-fired electricity declined from 2013 to 2015. As a result of overcapacity, bankruptcies surged in the coal-fired electricity sector, leading the government to focus on keeping the sector afloat through mergers. The National Energy Administration introduced a traffic light system in 2017 to prevent provinces with overcapacity from permitting new projects. The central government then moved to curtail approvals and suspend projects that had already been permitted. 27

But in 2019, as economic activity recovered strongly and trade tensions with the US grew, the Chinese government became increasingly focused on beefing up domestic coal supplies and prioritized employment and production. Approvals of new plants increased as the traffic light system was loosened. 28

- In 2018, six provinces were given a green light for coal power plant construction and three provinces were awarded an orange light. 29

- In 2019, 15 provinces were given a green light and two were given an orange light. 30

- In 2020, 19 provinces were given a green light. 31

Then in early 2021, the central government announced that it would strictly control “high emissions” projects, so permitting of new coal power projects was essentially frozen. The power crunch that hit over 20 provinces and municipalities in the second half of 2021 led to a reversal of that policy. 32

In 2021, the China Electricity Council estimated that the median age of China’s coal-fired power fleet was 12 years, with only 1% of the current fleet more than three decades old (the typical lifespan of a coal-fired unit). 3 Over the past decade, most of the new coal-fired power plants in China have been supercritical and ultra-supercritical. 34 Although the share of more efficient supercritical and ultra-supercritical plants has increased significantly since 2005, subcritical and less-efficient high-pressure and circulating fluidized bed (CFB) plants still represent almost half of China’s operational coal-fired power fleet. 35

China has not yet deployed CCUS at coal power plants on a large scale. (See Chapter 15 of this Guide.)

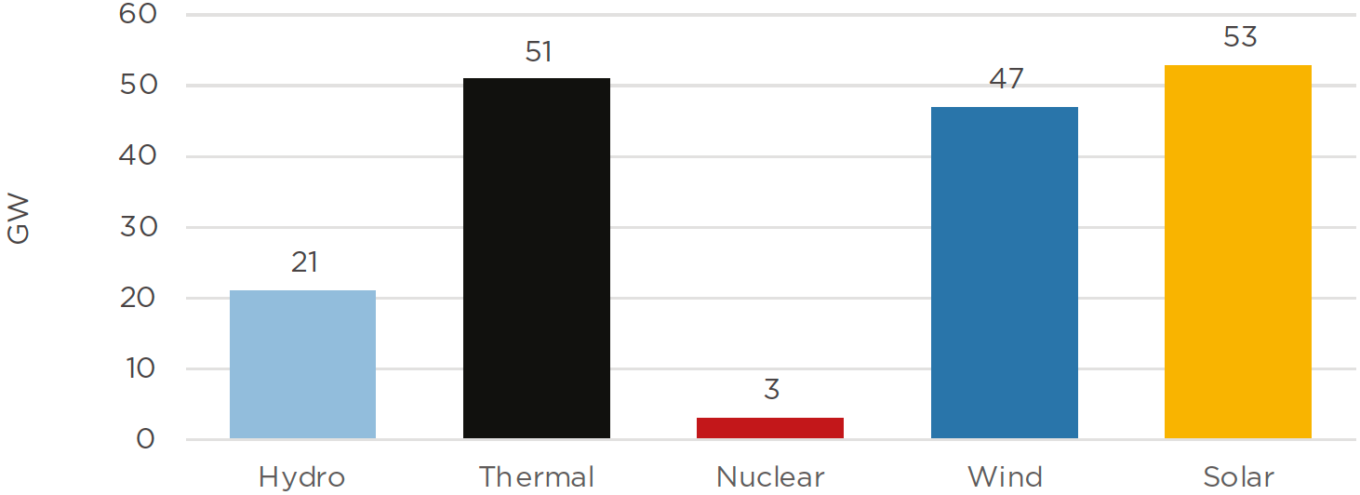

Figure 5-6: Annual Increase in Generating Capacity in China (GW) (2021)

Source: China Electricity Council 36

Coal Production

China produces more coal than the rest of the world combined, with roughly 51% of global production in 2021. According to official statistics, in 2021 Chinese coal production increased 5.7% to reach 4.13 billion tonnes. In the first half of 2022, it surged by 11% y/y37. During the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), coal production in China increased by an average of 2.5% per year. 38

In 2020, China’s proved coal reserves were estimated at 143 billion tonnes—35 years of production at current rates. China has the world’s fourth-largest coal reserves—after the United States, Russia and Australia—with roughly 13% of the global total. 39

In recent years, China has imported approximately 8–10% of the coal it uses, although net imports (the difference between total imports and exports) account for a smaller share of around 6–7%. In 2020, Chinese coal imports reached a record 304 million tonnes, only to rise again in 2021 to 323 million tonnes. China’s import requirements have been driven by factors including surging electricity demand, domestic transportation bottlenecks, economic factors (as imported coal can be cheaper than domestic coal in some coastal provinces), environmental and safety considerations, and concerns about depleting coking coal reserves. Chinese coal imports are roughly one-fifth of total global coal imports. 40

Coal Data Uncertainties

There are considerable uncertainties with respect to Chinese coal data.

- Chinese government agencies have revised their estimates of domestic coal production and consumption on several occasions. Some of these revisions have been substantial. Official estimates of coal production in 2000 are now 39% higher than the original number released by the National Bureau of Statistics. In 2015, official estimates of Chinese coal consumption for the prior decade were revised upward by 17%. 41

- Aggregate data from provincial authorities generally exceed national figures from the central government, sometimes by as much as 20%. Reasons may include double-counting of coal traded among provinces and inflated figures from provincial officials (whose promotion often depends on hitting GDP targets that have historically been correlated with coal consumption). 42

- Some Chinese coal consumption statistics are based on tonnage while others are based on thermal content. Trends with respect to each can vary, causing confusion. Estimates of the thermal content of Chinese coal sometimes differ, which can compound the confusion. 43

Policies

The Chinese government’s coal policies attempt to strike a balance between the goal of dramatically reducing coal use in the long-term and the economy’s continued dependence on coal in the short- and medium-term. While policies to reduce coal consumption often had the highest priority in the 2010s, in the past several years Chinese policymakers, while seeking to limit the share of coal in the energy mix, have also emphasized the important role they see coal playing in the Chinese economy.

During the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), China’s leaders introduced many policies aimed at reducing coal’s share of the energy mix, including capping coal use, removing dispersed coal from urban areas, switching from coal to natural gas heating across much of northern China, closing inefficient coal-fired boilers, tightening CO2 emissions standards and strengthening efficiency standards in power plants. 44 These policies principally targeted local air pollution. 45

One particular area of focus was “dispersed” coal (散煤), which includes coal used for home heating and cooking. Dispersed coal is effectively raw coal that has not been processed and washed according to strict standards. It combusts inefficiently and its emissions are not filtered before being discharged. Therefore, even though dispersed coal accounts for only 2% of China’s total coal consumption, it results in 5 to 10 times more air pollution per unit of energy than industrial coal. Dispersed coal is an important source of air pollution during the winter in northern China and became a focal point of government policies between 2014 and 2020. 46

In 2020, President Xi Jinping’s pledge to reach carbon neutrality by 2060 elevated decarbonization as a policy goal and sent a strong message about coal’s long-term future in China. In 2021, the Chinese government released its Mid-Century Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategy, which includes a goal of 80% non-fossil fuels in the energy mix. 47 While there are still questions about the potential role of coal with carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) in meeting these goals, the direction of travel has clearly been set.

This is reflected in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), which reiterates President Xi Jinping’s announcement at the 2021 Leaders’ Summit on Climate that China will “strictly control” coal consumption in the next five years, although the Plan does not set a limit on coal-fired power plant capacity in China or call for a halt to new construction. The 14th Five-Year Plan reiterates President Xi’s pledges to stop building coal-fired power projects abroad and gradually “phase down” domestic coal use in the next five-year plan period (2026–2030). These pledges are also discussed in China’s 1+N papers. 48

The pledge to “phase down” coal consumption was also included in the US–China joint declaration signed at COP26 and in the Glasgow Climate Pact. 49 These documents were the first international pledges ever made by the Chinese government to phase down coal consumption or coal power.

While these statements are significant, the 14th Five-Year Plan sets no limits for domestic coal production, consumption or power generation capacity but rather talks of “strengthening coal’s role as energy security guarantee…” and “the regulating role of coal power in the power system”. Instead, the 14th FYP says that coal power plants will be built or retrofitted as flexible rather than baseload power sources. The aim is to help regulate the fluctuations of renewables. By 2025, around 24% of all power generation capacity (3000 GW) will be “flexible power sources”, and at least 200 GW of existing coal power will undergo flexibility retrofits. 50 Unlike the 13th FYP, the 14th FYP does not include controls on the efficiency of coal power generation. (This may be because using coal power plants as flexible resources reduces their efficiency.) 51

The Chinese government’s renewed emphasis on coal dates back to at least October 2019, when Premier Li Keqiang, at a conference on China’s “new energy security strategy”, highlighted the role of coal more strongly than renewable energy. 52 In recent years, China’s leaders have reiterated the need to “give full play to coal’s role” in meeting the nation’s “basic energy needs”, to promote the use of coal in producing chemicals as a means of limiting reliance on imported oil; and that “clean and efficient” use of coal was “an important means” to achieving the country’s 2030 and 2060 goals. 53

The 14th Five-Year Plan also emphasizes coal production as a means of ensuring supply security. Although the Plan does not mandate output targets, it includes a goal for the country’s “comprehensive energy production capacity” to exceed 4.6 billion tonnes of standard coal equivalent. 54 Setting a target for capacity rather than actual production points to a greater emphasis on ensuring there are reserves for times of need. The Plan also discusses the need to optimize the layout of coal supplies by focusing on five large-scale and modern coal mines in Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi and Xinjiang. These will become China’s major coal supply bases as outdated, unsafe and inefficient coal mines are shuttered. In addition to the emphasis on energy production capacity, the government is looking to ensure a long-term “coal supply guarantee mechanism” which also includes reserve facilities.

So while China’s 2030 and 2060 carbon pledges clearly define a declining role for coal in the energy mix, the near-term trajectory for coal is complicated by the desire to use coal for supply security and concerns about the intermittency of renewable sources.

In 2015, large power generation companies were prohibited from emitting more than 650 grams of CO2 per kWh on average across all their plants. The 13th Five-Year Plan included a target of 550 grams of CO2 emissions per kWh by 2020 for these large power generators. 55 These standards required Chinese power companies to improve the efficiency of coal production, invest in low-carbon generation or both. 56 The 14th Five-Year Plan does not include a target for CO2 emissions per kWh.

NDRC sets targets for coal use per kWh in electricity generation and has steadily made those targets more stringent. In 2005, the target was 370 grams of coal per kWh; in 2020, it was 305.5 grams of coal per kWh; in 2021, NDRC set a target of 300 grams of coal per kWh by 2025. 58

China’s CO2 Emissions Trading System also encourages greater efficiencies in the coal-fired power fleet. (See Chapter 11).

Climate Change Impacts

China’s coal sector plays a significant role in global climate change.

- Coal produces more CO2 per unit of energy than any other fuel. 59

- China produces and consumes more coal than any country in the world, by far. 60

- Each year for the past decade, more than 20% of global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels came from coal combustion in China (as noted in the first paragraph of this chapter). 61

- In 2020, Chinese coal-fired power stations were responsible for more than 15% of global CO2 62

- Chinese coal production also produces methane emissions.

The Chinese government has ambitious plans to reduce coal consumption in the decades ahead. The pace at which it does so will have a significant impact on the world’s ability to meet its climate goals.

References